The history of Hungarian glassmaking

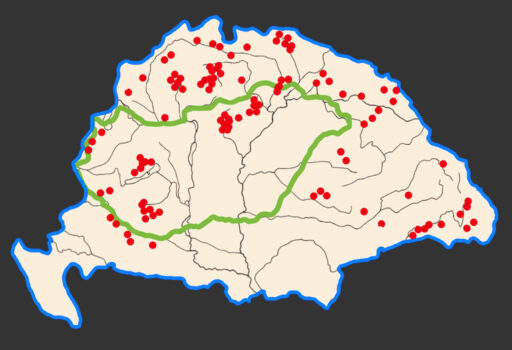

Hungarian glass-making is an alien subject for most foreign glass expert. Although the country has been truncated to one third of its original size after the 1st World War (Figure 1), during the history Hungary was an important state that shaped the shape of Europe, its industry including glass industry. Unfortunately glass articles were not the favourite items for Hungarian museums until the middle of 19th century. By the turn of the last century however the Hungarian National Museum had acquired a large stock of glass items that later moved to the Museum of Applied Arts, established in 1879, and public donations grew to stock to its current size. The first part of this 2 part article series tells the story of Hungarian glass industry from the beginning until the 18th century, and the second part will focus on the 19th and 20th century glass making including contemporary glasses.

The genesis and development of the independent Hungarian glass industry has started after the establishment of Hungary in 896 AD. In the Roman province, Pannonia, which was located in the western part of the Carpathian Basin, glass making began only after the 1st century AD. Articles for everyday use, such as cups, jugs and bottles for storing oil were mainly found in excavations in cities along the Amber road and in Aquincum (now part of Budapest). These hypothetical glass factories were destroyed during the Great Migrations and when the Roman Empire collapsed. Thus no articles from the factories can be found and we can only have indirect evidence of their existence from fragments of personal articles found in graves. In the era of migrations and conquest (around 895 AD) glass was used as jewellery, as glass beads and necklaces which were found in graves during archaeological excavations. Due to the high level of trading activity glass objects, mainly of Byzantine origin, reached the Carpathian Basin, and thus we still cannot talk about independent glass manufacturing process in Hungary.

After the foundation of the state and the adoption of Christianity (10-12th century AD) the church building started and monasteries brought the glass making the technology into the new country. From this period several artefacts were surfaced when the excavation of the former Benedictine monastery in Pásztó was started. Clues about the existence of glass works in monasteries were dug out. This was a building with 2 separate rooms housing 3 glass melting furnaces and kilns. The building contained space for preparation of raw material, drier and kilns. In Pilisszentkereszt, where the Pauline monastery and glass works existed in the 14-15th century more artefacts related to glass making were found. Other items were found in the eastern part of the Bükk Mountain where the names of places still reflect the heritage of glass industry (Nagyhuta, Kishuta, Répáshuta. Huta is the place where glass was manufactured). This shows that the glass manufacturing industry began in the area in the 12-13th century to produce sheet glass, although the blown-glass production to make items for home use started and spread at later stage. Of course this does not mean that the households did not use glass objects but they were imported from neighbouring countries. Glass works in Mátra Mountain and in the Esztergom county also existed but the importance of these are not significant and thus we will not discuss it here.

The first written records about glass manufacturing were found among Turóc county’s magistrate documents showing that in 1360 a glass master named Peter Glaser applied to receive glass making and timber permit. Another source shows the donation and later the sale of a glassworks in Teplice (now called Sklené Teplice, Slovakia). Teplice, like the rest of the Highlands area was part of the Kingdom of Hungary until 1918 (Figure 1). This document, dated on January 2nd 1549, proves that glassworks were existed for more than 200 years to provide glassware to store acid for gold extraction for the use of gold and silver mines located nearby. Thus, furnaces had already worked in the 14th century, and probably manufactured and served glass vessels used in mines producing precious metals. This fact is further argued by documents from the 14th century and also by names of towns, for example „Glashütten-Bad”.

In the 15th century the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire tried to occupy the southern part of the country several times. This was unsuccessful until the 16th century, when in 1541 with the capture of Buda (capital of Hungary) the 150 years of Ottoman occupation of Hungary had begun. The owner of the glassworks mentioned above sent a request to King Ferdinand to redirect master workers to his workshop because his masters dispersed and he did not know much about the practicality of the glass making. The history of this particular glassworks somewhere ends here, further data are not available. Where did the master of glass making go? For this interesting question the answer is even more fascinating. The Turks drove them to escape to Western Europe, and after wandering around in Europe a smaller group in 1556 ended up in Stourbridge, settled down and established a glassworks. This is still reflected by the name of an area in Stourbridge called Hungary Hill.

The glassworks in the 13th century manufactured articles for primarily used in the mining industry. Noble families looking after the territory were responsible to maintain the glassworks and provide wood for the glass furnaces. Only in later times we can talk about glassworks and masters of the industry who could produce everyday objects and stained glass windows.

During the Turkish occupation, the country was divided into three parts. The southern and central areas were deserted. Here neither ecclesiastical nor civil constructions could be conducted, so there was no demand for glass manufacturing. But in the western part of the country under the Habsburg power, and in the autonomous Kingdom of Hungary (Transylvania) the glass industry survived and evolved. Mining areas in the northern areas continued to require glass objects. To meet demand mining societies established local glassworks. Glass masters were imported from the Silesia region. One of the most important glassworks was established in Újbánya (Nova Baňa) in 1630. The centre produced bottles used not only in the mining industry, but also provided „glass disks for making windows” for the neighbouring area.

In addition to these glassworks, so-called estate glassworks were also established. These were founded by the aristocratic nobility primarily to meet the needs of their manor. But at the same time they saw a great investment opportunity in this business. The court in Vienna and of course the mining society running their own glassworks did not like the new establishment of private glassworks. The barons long tried to explain with extensive correspondences that this behaviour was „inappropriate for nobles”. One of the main arguments of the nobles was that they create articles only for amuse themselves. Of course it was only party true, and the glass production was also intended for trading.

Based on archaeological evidences and scarce contemporary descriptions these 16th century glassworks looked like the following: the glass factory was located in a wooden building that contained 3 kilns. The kilns had 3 different functions: drying the raw materials, workshop to do the actual work, and cooling furnace.

Glass items from the Medieval period are very scarce and unique. One example is the impressive goblet of King Mátyás (Mathias, 1443-1490) that it is now in the Hungarian National Museum, is the piece of Venetian glass making (Figure 2). The tip of the funnel-shaped thick-walled cup (42.8cm tall) runs into a node which is internally decorated by white threads. The base has been replaced with guided silver foot decorated with small turquoise-coloured stones. According to the verse engraved on the surface of the silver base, the goblet was of Venetian origin and they had a drink such times when they defeated the enemy. So it clearly had a ceremonial function.

In the south-west of the country, Bajcsavár (now Weitsch-war) was one of the most important border fortresses at the end of the 1500s to suppress the Turkish attacks. The castle was mainly built from the support of the Styrian estates. The archaeological excavations of a pentagon-shaped fort have surfaced several glassware in Italian style, which were intended for the lords in the fortress. Footed drinking glasses with white stems, cylindrical beer glasses and conical twin-bodied brandy bottles were found. They were produced in the nearby Styrian workplaces.

We have to mention the Transylvanian glassworks where approximately from the 15th century important glass production took place. In the 16th century manufacturing of window glass, stained glass and trading with glass articles were common place here. Later, in the 17th century the Transylvanian glass window production had considerably increased. The main reason is that numerous natural disasters – especially fire – stroke the region, and also the number of new manor houses increased that required more glass windows. The technology to produce plate glass was imported from Vienna and according to contemporary statements local glassworks produced plate glass in 1634.

Since the Turkish occupation lasted for 150 years, in the 17th century Hungarian glass production was mainly confined to the manufacture of window glass and artistic glass making was not developed. Glass objects for household use were obtained from Bohemia-Moravia, Poland and Vienna. The only exception is the so-called “cellar flask” which are mold blown bottles that fitted in a container. As the name indicates a wooden case containing usually 6 padded compartments housed these bottles. These were used to store and to transport wine and other household liquids. In the 16th century these bottles were made of colourless glass without decoration. By the 17th century these were became “independent”, left the container and various engraved, and enameled motifs decorated them (Figure 3 and 4). Obviously the blown glass manufacturing was not restricted to cellar flask and “klukflaske” or Kuttrolf (“kotyogos” in Hungarian) was also produced (Figure 5). A third type is a glass decanter with externally applied glass trail decoration dividing the bulbous body into six segments. These parts are engraved with peacock and grape motifs (Figure 6). The shape but not the decoration is similar to Dutch decanters from the same period, which are more common. This type of flask can still be found in second hand and flea markets and were made by German glass blowers in Porumbak from 1650 onwards to present days, thus the correct identification is not easy.

Only three glassworks are mentioned in written documents in the southern part of Transylvania: Rozsnyó, Olthévíz and Talmács. Under the ruling of Gábor Bethlen, lord of Transylvania, several glassworks were established alongside the Olt river between his election in 1619 and his early death in 1629, in which the lord himself invited Venetian glass masters. These masters left Transylvania and returned to Venice after the death of Bethlen. The proof of this event is that a contemporary historian, Georg Kraus, met the craftsmen in Venice who previously worked in the glassworks in Porumbák. After the death of the lord they left the place because of the economical uncertainties and harsh treatment by the local officials. This fact is certainly not equal to the closure of the kilns, only temporary suspension of glass production and in 1648 they restarted the glass manufacturing process. In this century the tinted glass, i.e. the cobalt blue glass, appeared. Where to obtain the cobalt was not a problem, since a significant amount of cobalt was mined in Transylvania. In fact, these mines provided cobalt to most of Europe. The main purpose of using colour in glass manufacturing is to mask the weaknesses and errors made during the production. This is also the period when opal and milk glasses appeared (Figure 7). In is interesting that the so called Haban ceramics had great impact on glassmaking. The ceramics made by the Habans (German catholic religious sect) were of the following characteristics: the tin-glazed body was decorated with four basic colours, purple, red green, and yellow. Since the glass making and decorating workshops had insufficient equipment to perform a sort of glass decorations, so they did it in the Haban pottery. So the glass was decorated with similar methods as potteries resulting milk glass appearance but in fact these glasses are tin-glazed (Figure 8).

From the second half of the 17th century with the emerge of Czech crystal glass the glass crafts has evolved and separated into different professions. From the mid-16th century a new profession, the glass decorators have emerged. As the documents of contemporary glassworks did not include any tools used in the decoration, engraving, or painting, we can assume that the decoration took place in a separate workshop as an individual profession (Figure 9).

Overall, the historical events and technological developments in the 13-16th centuries paved the way for the heyday of Hungarian glass making in the 19-20th century which will be covered in the next part.

The method of Hungarian glass making reflected the hegemony of Venetian blown glass and Czech-Moravia and German crystal glass styles. The aristocrats and well to do civic families required the high quality richly engraved and brightly coloured glasses that decorated the dining table and could be placed on mantel piece. Small glass workshops using the wood-burning furnaces were unable to produce clear crystal (lead) glass and they continued producing items for the peasant population. Larger glassworks, or smaller workshops with enough capital to modernize the furnaces adopted the Siebert type regenerative heating system and gas-tank furnaces. This modernization was often the last option for survival because wood supply started to dry out due to the uncontrolled cut down of nearby forests. The producing manorial glassworks, which moved often from one wooded estate to another, and some isolated forest glasshouses developed continuously in the course of the 19th century into glass factories.

One of the most important glassworks was in Northern Hungary in Zlatno where János György Zahn ran his factory and was an important figure in the Biedermeier style glass making business besides Lobmeyr and Perger in Austria. The name of this factory is associated with iridescent glass because the brilliant inventor Valentin Leo Pantocsek extensively worked here. Pantocsek (1812-93) was a medical doctor who received his degree in 1843. He became fascinated by the newly developed form of photography known as a daguerrotype. First he worked in a glass factory owned by Stefan Kuchinka, in Utekac. There, in 1850, he developed the hialoplastic method, which he used for making glass coins that were among other uses embedded in glass beakers and chalices. Admired for their extremely fine level of detail and sharp pressed lines mostly depicting profiles of persons, they won a gold medal at the Paris World Fair in 1855. Pantocsek took the secret of manufacture to his grave and surviving examples are not known, or hidden in private collections.

In 1856, already working in Zlatno in Zahn’s factory, he extended his existing technique or developed a new one to iridise blown glass vessels (Figure 10). The first iridescent works were shown and lauded at the lesser-known 1862 World’s Fair in London. His native country did not hold his development in as high regard, and it was largely ignored, but the opportunity was spotted by the Austrian Josef Lobmeyr and his brother who owned the esteemed glass company J&L Lobmeyr in Vienna. They saw a future in the glass finish and ‘enticed’ one of Pantocsek’s glass-making colleagues away and thus learned how to make iridised glass. The Lobmeyr brothers passed this information on to their brother-in-law Wilhelm Kralik, who produced the glass for them at his factory. In 1873, Lobmeyr displayed a huge range of iridescent glass at the World’s Fair in Vienna where it received international attention and met with great success. Zahn’s Hungarian factory didn’t stop producing iridescent glass, but although iridescent glasses were exported even to the United States, his reach was not wide to make any impact.

As Pantocsek didn’t write his recipe down, the company ceased production after his death in 1893. The bright and irising surface effect of this type of glass exerted its influence in the European Liberty style art nouveau endeavours and in the experiments of lustre to create metallic surface on the glass carried on by the American Louis Comfort Tiffany.

The Hungarian glassmaking, apart from the adoptation of the international stylistical characteristic of the historical genre, elaborated also its particular national qualities out of Hungarian motifs, which predominated strongly under the Liberty style too, even after the end of the 1900-ies.

The 19th century brought important changes to the Hungarian glass industry from another point of view, too: the separation of the glassmaking and ornamenting workshops mainly at Pest-Buda (the name used before 1872, after Budapest) taking shape from the middle of the 19th century. One of the most renowned glass decorators who extensively used Hungarian motifs was Henrik Giergl (1827-1871) trained at Lobmeyr in Vienna. The Giergl shop was established by his father in the heart of Pest in 1820. They had a keen eye for quality and apart from their own high quality glass items the shop also offered Daum and Galle masterpieces for the wealthy clients. The apprenticeship at Lobmeyr left its mark on his style: clear, precise, and beautiful design characterize his works reflecting the popularity of the combination of Hungarian historicism, the use of national style and oriental designs (Figure 11). The store operated until 1910.

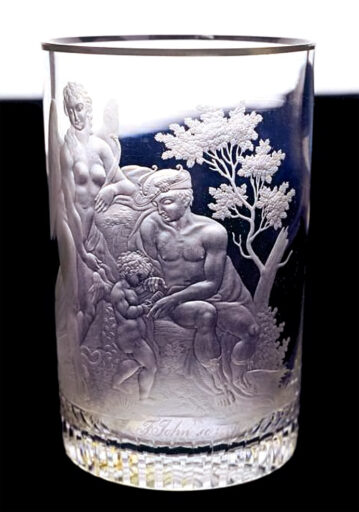

The profound influence of Czech glass making in the 19th century was reflected in the glass items produced in Hungary. Glass cutting and engraving was masterfully exercised in Bohemia, techniques that required special technique, talent and equipment. Not surprisingly large number of glass with Hungarian motifs, famous Hungarian persons or depicting buildings in Pest-Buda were made abroad and exported to Hungary. Only a handful of glass engraver masters worked in Pest-Buda, most notably József Oppitz. The family probably originated from Moravia, and after a long wandering he settled down in Kassa (now Kosice) in the first half of the 19th century where he joined the glass guild. Most of his works are still in private hands thus we have limited information about his art (Figure 12). He is considered the most significant glass engraver of Northern Hungary. Another important engraver who worked in Pest around this time was József Piesche. He was born in Steinschonau and settled down in Pest around 1821 where he worked not only as glass engraver but also as precious stones cutter. His artistic talent was rooted in the transposition of the gemstone cutting technique into glass engraving (Figure 13). His work had greatly influenced not so much his contemporaries but the next generation of engravers. He was conscious of his talent and always signed his works.

István Sovánka (1858-1944) was the only glassmaker in Hungary who followed Gallé’s cameo technique in the 19th century working in the Zayugróc glass factory. Unlike Gallé, he used multiple very thin layers of coloured glass on colourless or lightly coloured base glass that was acid etched and sometimes treated to achieve iridescent surface (Figure 14). He won gold medals at World’s Exhibitions in St. Louis in 1904 and in 1906 in Milan. Around in 1908 he moved to Sepsibükszád’s glass factory as a joint tenant, and worked here until the outbreak of the First World War. After 1914 he returned to his original profession of woodcarving and created wood sculptures.

In the 1860’s, a new glass style was adopted in Hungary with the promotion of Ágost Trefort, Minister of Education, which was stained-glass making and reached the level of the highest international quality by Miksa Róth’s work of art, ‘the imperial and royal glasspainter’ (Figure 15). The high level of stained glass art of that time was acknowledged with e.g. Róth’s silver medal he had won at the 1900’s World Exhibition in Paris. His work decorated tea houses, mansions and villas and still can be seen in important buildings such as in the Hungarian Parliament, Hungarian National Bank and benedict Abbey of Pannonhalma. The industrial exhibitions (1842, 1843, 1846) by Kossuth’s society also gave inspiration to the glass industry, or, in the matter of this, the world exhibitions – especially London’s in 1862, Vienna’s in 1873 and Paris’ in 1900 – were the ones of outstanding importance because the Hungarian factories met with significant success, their work won medals.

Based on archival data, we can say that glassworks operated in the Matra mountains since the 16th century. But they were not really significant, since due to the logging of the surrounding forest they continuous migrated, and in course of time they completely disappeared. In this region only one factory survived in Parád. The factory, that still in operation, was founded in 1708 by prince II. Ferenc Rákóczi who was the owner of the land. In 1711 the factory ceased production and restarted only in 1727, and then in 1767 was moved to its present location: Parádsasvár. As some information was forgotten in history , so it was possible that the factory in 1964 celebrated its 150 year anniversary, because for a long time it was believed that the factory was founded in 1814. After the relocation the factory began to develop, and the Parád glass products were wildly known in the 1780-90’s. In 1803 the workshop was fitted with engraving and cutting equipment, which allowed them to produce artistically decorated lead crystal items. In 1819 the factory was rebuilt and modernized resulting in higher volume and better quality products. Parád products started to be exported in volumes mainly to Balkan countries. 1840 was another milestone in the history of the Parád glassworks, as from this year the factory was owned by the count Károlyi family, and this was the first year to have inventory. Moreover, at this time the area of Parád began to flourish because popularity of the spa. The Parád factory spotted a business opportunity and produced large number of souvenir items for the guests of spa including memory beakers and glass for thermal water drinking (Figure 16). Other souvenir items such as vases, beakers that reminded the guests for the stay were also mass produced (Figure 17). Here we have to mention the spreading popularity of medicinal bathing during this period, as this type of recreation greatly impacted on glassmaking. In 1688 Queen Anne Stuart after suffering another miscarriage she left London to recuperate in the spa town of Bath. This event is considered to mark the beginning of the spa culture in Europe (other sources mention 1702). At first, the spa culture began to spread in the aristocrat circle and was more of a social event rather than a form of healing exercise. Later, due to the development of rail networks it has become more affordable and accessible to the circle of civics. In the 19th century Europe particular attention was focused on the composition of the thermal waters, and places where mineral and the thermal waters were consumed became wildly popular. With the development of medicine therapies were supplemented with the consumption of thermal waters, exercise and diet, and thus a new industry began to emerge. Glass factories produced beakers and glass cups decorated with views and the name of the spa (Figure 18). The style of the early Hungarian bath cups around 1820 reflected the Biedermeyer taste with thick-wall and round base. From the 1850s the forms and the decorations become more elaborate. But to return to the history of Parád glassworks: in the National Exhibition in 1846 the factory won the silver medal with its products. Moreover, with the continuous development of the Károlyi family Parád was among the first glass factories where the switch of the use of soda to potash, and from the firing of the kilns from wood to coal happened. This developmental process was interrupted by the break out of the First World War, but the factory kept producing interestign and characterisitc glass items thorough the 20th century (Figure 19)

Another major factory was established in the 19th century that still produces glass in the 21st century. Bernát Neumann established the Ajka factory in 1878 with 40 workers and a steam engine – which was the “modern” technology at that time in Hungary -, after the predecessor of Ajka’s factory at Úrkút (a small village near to Ajka) closed down in 1876. In the 1880s the factory won numerous prizes at national exhibitions with their lamp cylinders, wine glasses, everyday glass items and cut glasswares. That time they also made cased, gilded, pressed, enamelled and iridescent glasswares, scent-bottles and table glasses. In 1891 the factory was changed the owner to János Kossuch and Sons and the factory flourished. The turn of the 20th century Ajka Glass Factory changed their productions line in two directions: for working of hot – furnace-ready glass – and for working of cold glass. The factory still produces glass items; part is under Ajka brand name but many for export including Faberge, Dior and Waterford. The exported items contain only the target brand name, and not Ajka and thus without having access to the factory’s archive we are not able to know exactly what Waterford glass is actually made in Hungary.

In 1896 the numerous exhibition and programs took place to celebrate the 1000th anniversary of the establishment of Hungary as a state. In the Millennium Exhibition 16 glass factory participated and exhibited their newest products. The Ajka Glass Factory created a glass copy of the Holy Crown of Hungary, which was a technical feat at the time. The glass crown is now in the Museum of Applied Arts (Figure 20) while a copy that was produced at the end of the 20th can be seen in the museum of the Ajka Glass Factory.

The evolution of technology in glass engraving and cutting enabled the glass masters to produce highly artistic glass objects. Apart from the already mentioned József Oppitz and József Piesche a number of talented engravers and cutters worked in different parts of the country, who immortalized significant events on glass beakers, cups and vases. Such event was the Great flood of Pest in 1838, the revolution and war of 1848-49, and portraits of eminent personalities related to the revolution, but objects depicting ‘simple’ townscapes, and landscapes are also not uncommon. These objects are not only intended to depict the era and the nature, but also served as a gift to high ranking officials in prominent positions to gain their “goodwill” and smooth the way to win a case during intervention.